What do the Olympics have to do with Olympia, the German manufacturer of typewriters?

From Cortina d’Ampezzo to Erfurt to Berlin – and from Hitler to Heinz Prygoda. How a German typewriter company turned Olympia into a global brand.

The Olympics are all about emotions, triumphs and records. This year, Cortina d’Ampezzo and Milan are hosting the renowned Winter Games. The guardian of the Games is the International Olympic Committee (IOC). It knows how much the Olympia brand’s worth – and is protecting it accordingly.

Only official partners and sponsors are allowed to use the Olympic rings, the terms «Olympia», «Olympics» and «Olympian» as well as «Paris 2024» or «Milano Cortina 2026».

Rule 40 details what athletes are allowed to do, when and how personal sponsors may be shown and so on and so forth. The regulations include several page-long documents.

How Hitler exploited the Olympics

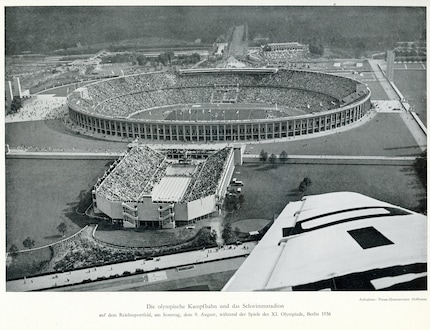

These strict regulations make sure what the Nazi regime did 90 years ago couldn’t happen again today. The 1936 Olympic Games took place in Berlin, in the German Reich, which was ruled by the NSDAP with Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The National Socialists knew about the power of the Olympic idea and unscrupulously used the world’s biggest sporting event for their propaganda.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The aim was to promote physical strength and the cultivation of healthy bodies for a healthy so-called national body – all with the deployment of German soldiers in mind. The German people were to gain new self-confidence through successful Olympic games. The plan was for the world to see a well-organised, clean, peace-loving and cosmopolitan Germany. The regime decreed that everything anti-Semitic had to disappear from public view during the games. Although the IOC warned the Germans not to misuse their role as hosts for self-promotion, the regime did everything it could to show itself as a masterpiece of propaganda.

From sports to typewriters

That brings us to typewriters. I’m pretty sure none of the people who decided there should be a typewriter named Olympia Modell 7 are still alive. That was in 1931. I’d have loved to have been a fly on the wall at that meeting. The predecessor model was simply called AEG Model 6 and was built in the Europa Schreibmaschinen AG factories in Erfurt.

In 1936, «Olympia» was even added to the company name, making it Olympia Büromaschinenwerke AG, Erfurt. The same year, the Berlin Summer Olympics as well as the Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen took place. In other words, the entire country was in an Olympic fever. Olympia wasn’t a protected term, so it seemed an obvious marketing idea to use its popularity. Car manufacturer Opel had the same idea and launched the Opel Olympia in 1935, one year before the games.

Why Erfurt ran into problems after World War I

Erfurt, capital of the federal state of Thuringia, with a population of 220,000, was a kind of Silicon Valley of its time at the beginning of the 20th century. I talked to Dr. Steffen Raßloff, who gave me insight into the city’s industrial history. According to the historian, a large proportion of the pistols and rifles for the soldiers of the German Empire were produced in Erfurt until the First World War ended (page in German). The Königlich Preußische Gewehrfabrik (Royal Prussian Rifle Factory) had been operating in Erfurt since 1862 (page in German). Dr. Raßloff told me that two thirds of the soldiers in the First World War were equipped with weapons from Erfurt – revolvers, needle guns and carbines.

After Germany’s defeat in 1918, that all came to an end. The Treaty of Versailles of 1919 stipulated that, with very few exceptions, Germany was no longer allowed to manufacture weapons. Attempts were made to circumvent the ban – the factory in Erfurt kept producing pistols. But in 1923, the Allied Control Commission banned this, too.

What to do? According to Dr. Raßloff, 20,000 employees were out of work. All well-trained specialists, precision mechanics who had mastered the craft of producing weapons.

New work for specialists

These former weapon manufacturers then became manufacturers of office machines. AEG from Berlin saw the opportunity and took a stake in the new Deutsche-Werke-Schreibmaschinengesellschaft mbH, which was renamed to Europa Schreibmaschinen AG Berlin – Erfurt in 1930.

The company was at the right place at the right time and with the right products. In the following years, a booming market was served from Erfurt. The Mignon model was produced from 1924. The original model had been around since 1904, at that time still produced by AEG in Berlin. However, the machine was improved in Erfurt. By today’s standards, everything happened very slowly. By 1933, that’s over a period of 29 years, only four new models had been launched. And the last model, the Mignon 4, was sold from 1924 to 1933. Imagine a smartphone manufacturer not launching a new model for that long.

Nevertheless, the success was immense. Between 1936 and 1938, the factories in Erfurt produced more typewriters than all other manufacturers in Europe combined, according to Dr. Raßloff’s research.

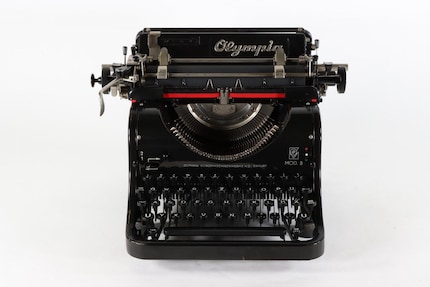

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The successor model of the Mignon was called AEG Model 6. It launched in 1925 and wasn’t named Olympia until 1930. It’s a typewriter with a keyboard, basically what we still know today. The Mignon, on the other hand, was an index typewriter, which worked by using a pointer to manually select characters.

Source: Chemnitz Museum

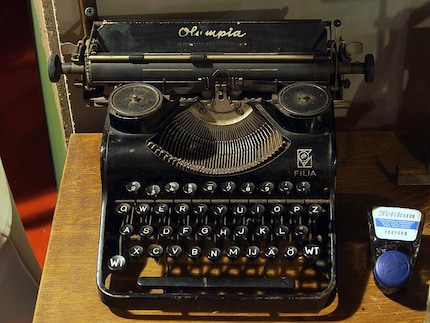

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Other models from the Erfurt factory were called Filia, Elite and Progreß. These were portable typewriters. A brief excursion to Switzerland: the most famous portable typewriter model was the Hermes Baby, manufactured by the Swiss precision engineering company Paillard at the time. For well-known writers such as Ernest Hemingway or Max Frisch, that typewriter was what the laptop is for us today.

Source: Shutterstock

Why Erfurt built the Enigma

However, the National Socialists changed their minds about the factories in Erfurt. During the Second World War, Olympia produced weapons again. And a very special kind of typewriter: the Enigma. Its construction required certain skills that the workers in Erfurt had.

The fact that the encryption machine was manufactured in Erfurt had to remain secret during the war – and the workers were forced to sign contracts to assure this. The Enigma was essential for the German navy to communicate with its submarine fleet via encrypted radio messages. Meanwhile, the British wanted to crack the code as quickly as possible. They achieved this in several stages between 1940 and 1942.

Not long ago, an Enigma was auctioned in London. Dr. Raßloff told me this auction was a painful experience for him, as he’d have liked to have it for the Erfurt City Museum. However, the machine went to a bidder who offered more money than the city could afford.

Source: Bonhams

The Enigma’s been the subject of many stories since the Second World War, inspiring authors to write books and make films, for example Alan Turing: The Enigma, which was filmed in 2014 with Benedict Cumberbatch in the lead role.

How the split came about after the war

In 1945, the Second World War ended and Germany surrendered. The city of Erfurt hadn’t been destroyed by bombs. However, the Olympia works burned down after artillery fire during the American invasion.

The workers set about repairing the damage and soon resumed the production of typewriters, now operating as a Soviet joint stock company. In 1948, the Olympia factory had already produced around 64,000 typewriters, which was 60 per cent of pre-war production. Around 4,500 employees worked at the assembly lines.

From 1950, the Erfurt workers were no longer employed by Olympia, but by VEB Optima Büromaschinenwerk Erfurt. After 1945, some former Olympia employees from the Soviet occupation zone fled to the West, taking with them important design documents. They established a new Olympia factory in Wilhelmshaven. A legal dispute ensued over who was allowed to keep the name. The winner, as decided by the International Court of Justice in The Hague, was Wilhelmshaven. This was the start of a new era, as Dr. Raßloff says:

From then on, Optima and Olympia were fierce competitors.

In its heyday, from around 1950 to 1970, 20,000 people worked in Olympia’s typewriter factory in Wilhelmshaven – and over 6,000 at Optima in Erfurt. While Olympia was Europe’s market leader for a while, Optima ranked fifth in the world in 1963, according to the company’s yearbook. In the Erfurt City Museum, numerous models bear witness to the global success, including some typewriters with Chinese, Indian and Japanese keyboard layouts.

How digitisation ended everything

The year 1979 was both a peak and a turning point. Optima was one of the first companies in the world to introduce an electronic typewriter, the Robotron S 6001. From the 1980s onwards, digitisation began and personal computers emerged. This was the beginning of the end for typewriters. From then on, tasks that typewriters had previously combined in one device were done separately.

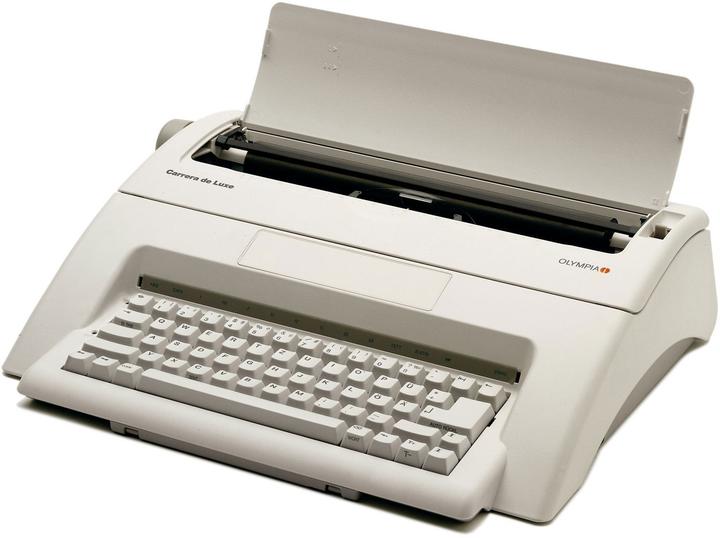

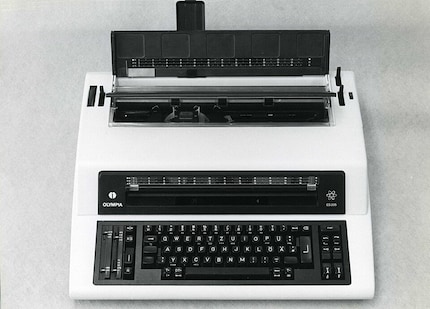

Olympia’s management wasn’t prepared for the digital transformation and had no solutions at hand. The company shut down soon after, with the last Olympia ES200 typewriter being produced in 1992.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Optima also closed its production doors shortly after German reunification. Before that, VEB Optima had been privatised and transferred to Robotron Optima GmbH. In 1992, some managers bought themselves out and founded Optima Bürotechnik GmbH. However, this company went bankrupt in 1999.

Who still uses typewriters

Until 2003, typewriters still played a small economic role, as they were among the products used to determine the consumer price index. At that point, however, they’d already become virtually irrelevant in everyday life, with computers and printers having taken over their job.

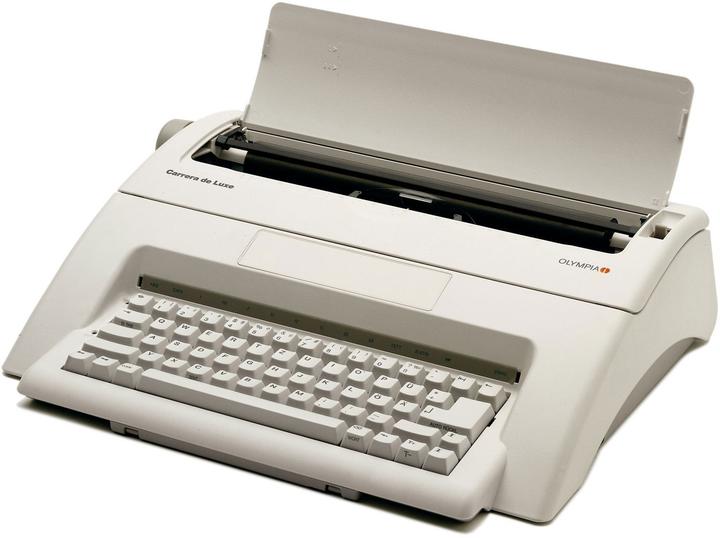

While a million typewriters were sold every year in the 1980s, sales have now fallen to around 10,000 per year at best. Having said that, you can still buy typewriters on Galaxus, even ones made by Olympia. But let’s not mention the sales figures.

So who still buys typewriters? Maybe some authorities that persistently or deliberately refuse to embrace digitisation. I’m thinking of special pre-printed forms that can only be filled out with a typewriter carbon copy. Security agencies might also buy typewriters because they keep secret files.

Today, entrepreneur Heinz Prygoda’s the face behind the once-great name Olympia. A few years ago, he secured the rights to the name, which had been held by a limited company in Hong Kong. As a result, Olympia products are made by Prygoda’s company Go Europe GmbH. Nothing’s European about that company except the name. Most of the production takes place in China. Of course. In addition to typewriters, which still account for five per cent of sales, Olympia produces telephones with large buttons, document shredders and laminators, for instance.

So, while the IOC strictly protects the Olympia brand and a billion-dollar business has developed around it, Olympia office equipment’s now just another commodity from China. What a paradox!

Journalist since 1997. Stopovers in Franconia (or the Franken region), Lake Constance, Obwalden, Nidwalden and Zurich. Father since 2014. Expert in editorial organisation and motivation. Focus on sustainability, home office tools, beautiful things for the home, creative toys and sports equipment.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all