Background information

Our favourite items of 2025

by Samuel Buchmann

Building my living room gaming PC revealed how cramped and demanding a 20-litre system can be. Between fans, a power supply unit and an oversized graphics card, there’s barely any room for manoeuvring. But this just makes the moment when my system finally comes alive all the more exciting.

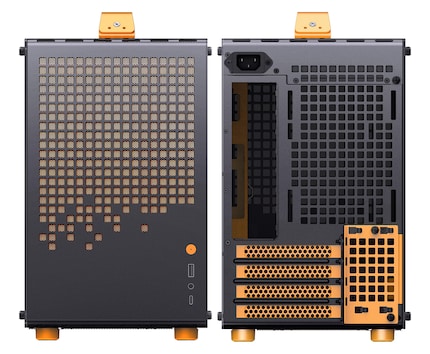

The plans for my living room PC revolve around one goal: ending up with a Linux-based high-end system that feels like a gaming console and delivers a Steam OS experience that mops the floor with the PS5 and its ilk. Now comes the practical bit – the build. The components are ready. Just as an example, there’s 64 gigabytes of RAM for oversized Skyrim mod packs, fast SSDs for short loading times and a large Noctua cooler for quiet operation in the living room. Everything makes sense on paper. However, as I open the Jonsplus Z20 housing, I quickly realise how cramped a small 20-litre system really is.

Between fans, a power supply unit and an oversized graphics card, there’s barely any room for manoeuvring. Some movements require more feeling than sight, and beads of sweat form on my forehead in several places – not out of panic, but out of respect for the precision this case demands. But it’s precisely this mix of planning, improvisation and tricky moments that makes the build so exciting. And yes: in the end, the system actually comes to life, but only on my second attempt. In retrospect, a different power supply unit would’ve made things much easier.

One small side note: I had already ordered most of my components at the start of October – a stroke of luck when you look at today’s prices. I only assembled my PC over the festive period, due to a mix of little free time and a hope that Noctua would deliver their latest fans in black in time. Sadly, this didn’t happen.

The centrepiece of my build is an MSI B850M Mortar WiFi mATX main board. I chose it for three reasons. First, the current AM5 chipset offers enough future-proofing without drifting into experimental territory. Second, the integrated 5 Gigabit Ethernet port is perfect for a Linux-based high-end system. Third, and don’t underestimate this point: my board is black. Combined with the Jonsplus Z20 housing and its glass side panel, this results in a harmonious overall impression untainted by random colour accents.

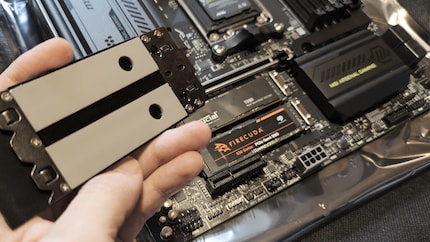

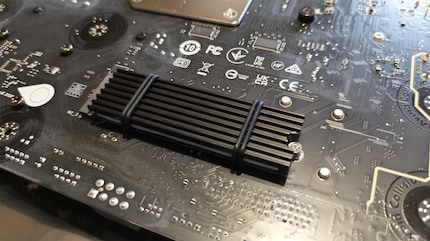

Before the main board’s installed, I equip it with the parts that are most convenient to add outside the housing. I begin with the three SSDs – each with a clear task and deliberately chosen:

Two of the SSDs sit on the front of the board under the cooling cover, which snaps into place flush. The third seems to have moved to the back, on top of getting its own cooling element, an Axagon Aluminum Heatsink (CLR-M2L3).

Next up is the RAM: Kingston Fury Beast, 2 × 32 GB, DDR5-RAM, DIMM, 6000 MT/s, CL30, black, matching the rest of my build. I chose 6000 MT/s deliberately, since this clock rate should offer the best compromise between stability, latency and real performance on AM5 systems. Higher clock rates rarely offer any benefits, but lower ones often lack performance. And 64 GB isn’t excessive: after all, I’m looking to play a highly modded version of Skyrim. And the Skyrim mod pack I have in mind is set to devour half of my SSD on top of consuming my RAM like a black hole. I deliberately avoid RGB LEDs in my RAM – I want my GPU to be the only illuminated element in the end, a clearly set accent instead of a light show.

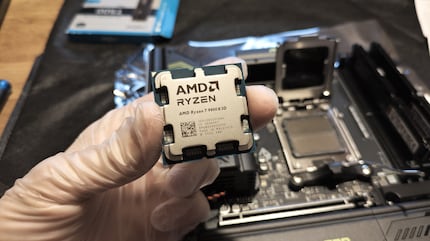

Finally, the AMD Ryzen 7 9800X3D slots into its socket. A simple choice: there was no better way to game on Linux at time of purchase. The 3D-V cache architecture delivers exactly the kind of performance a Steam OS-like system needs for living room use – high frame rates, fast load times and efficiency worth its weight in gold, all in a compact 20-litre case. In addition, there’s another benefit: experience has shown me that Linux runs smoother with AMD than Intel thanks to its simpler architecture and stable kernel integration.

The CPU cooler will come later, when my main board’s fully installed – even if my fingers are itching to finish everything right now.

The build is picking up speed, and the board is ready for the next step.

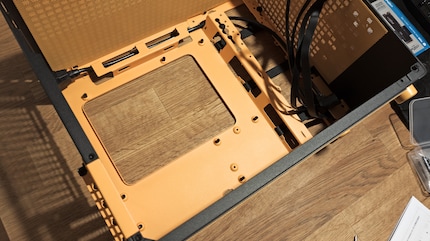

Before my main board finds its way into the Jonsplus Z20, I first remove the fan frame on the top of housing. This adds some freedom of movement – a small but crucial luxury in a 20-litre case.

The frame moves to the side and the main board spacers come into view. Some of them are already placed correctly, others I have to move. A quick alignment with the mATX layout, a few turns of the screwdriver, and everything’s ready.

Now comes the moment when my main board slides into the case. A calm, focused movement. The edges of my board find their way over the spacers – a gentle lowering, a soft click, then the screws. It fits.

I then lay the front panel cables and connect them to the board.

I grab a cleaning cloth and remove the last traces of dust from the CPU surface. Now I turn my attention to the largest Noctua cooler that’ll still fit into the case height-wise. The NH-U12A chromax.black has two 120 mm fans in a push-pull setup. I’m expecting it to deliver rich cooling performance coupled with quiet running worth its weight in gold, all in my living room.

Next up, Arctic MX-6 thermal paste: one larger dot in the centre and four smaller ones at the corners of the heat sink. I carefully place the cooler on top, screw the bracket in place and fit the two fans. A click here, a cable there, and the thing stands like a black monolith in the centre of my build. It seems almost oversized – until you remember how much power is packed into this small case.

With the cooler installed, the fans connected and a final check, the main board is finally ready. Soon the power supply unit, cable bulges and graphics card are fighting for every millimetre.

Next, I reach for the Enermax PlatiGemini 1200 Watt 80 PLUS Platinum. A power supply unit that seems almost oversized for this small housing. I attach it to the front of the Z20 and screw it in place. The internal mains cable, which runs from the rear to the front, is already neatly positioned in its designated channel.

I position the power supply unit so there’s still enough space above it for the two upper system fans. Annoyingly, they won’t fit next to it if they’re installed any later. The power supply unit itself is oversized in terms of performance: even potential future system upgrades will never be able to utilise it fully. I ordered it because it’s apparently most efficient between 20 and 50 per cent utilisation. Hopefully, this’ll have an effect on longevity. In addition, I shouldn’t ever hear the fan this way.

Then comes the wiring. The supplied cables are pleasantly thin sleeved. I prefer thicker cables, but I’m glad I don’t have anything like that to hand today. Still, the sheer abundance of thin cables directly around the power supply unit leads to tight spots. I have to push and shove a little until everything fits through. Beautifully laid out? Forget it. But who cares? After all, nobody will see the mess anyway when the case is closed. In retrospect, I still would’ve preferred a more compact power supply unit. I can already see how tight things will get for the graphics card, the rear part of which will be located under the power supply unit.

Next, I mount my two Noctua NF-A14 PWM chromax.black fans at the top of the case to extract any warm air. The fans are supplied with vibration pads in different colours, but only four per colour, meaning you’ll always have to combine shades. You’ll need eight pads per fan. To ensure everything fits seamlessly into my build, I replace the colourful pads with black Noctua NA-SAVP1 ones. I screw the fans to the fan frame, push it back into the case like a drawer and screw it down. Following that, I connect the two fan cables with a PWM-Y splitter (Noctua NA-SYC1 chromax) and connect them to the same PWM header on the main board. This allows me to modify both fan settings simultaneously when creating the fan curve in the UEFI later.

The rear housing fan follows: a Noctua NF-A12x25 PWM chromax.black. It’s again fitted with black pads, screwed into place and connected.

Incidentally, I went with Noctua fans because I’ve had good experiences with the brand. But they also offer high static pressure, very quiet operation and reliable cooling at low speeds in this narrow case. Unfortunately, there’s no room for extra fans at the bottom of the case, since the graphics card would be too large or would sit too far down. Looks like the GPU fans will take on the job of bringing air into the case. Not ideal, but it’s unavoidable given the form factor.

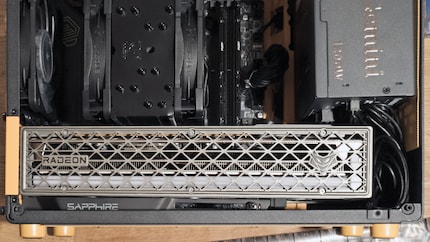

For my graphics card, I opted for the Sapphire Radeon RX 9070 XT Nitro+. It’s considered one of the quietest cooled cards in its class – a crucial point for a living room PC that should be quieter under load than the PS5 Pro. It offers plenty of power without the typical hairdryer noise of many high-end models.

The power connection for the graphics card is located under the magnetic backplate. I detach it, feed the cable from below into the 16-pin port hidden on the side and replace the plate.

The PCIe slot and its locking mechanism are clearly visible and accessible before the graphics card is inserted. I press the button to unlock the slot and start carefully inserting the card. Fortunately, with a little help and some bendy cables, it fits under the power supply unit. However, due to the large fan and the card’s proximity to the bottom of my case, I can no longer see the slot when I slide it in. From there on out, I’m flying blind. I can’t see if the card is properly seated in its slot. I orientate myself by using the horizontal top edge and feeling the card, finally pressing the locking button accidentally. It stays in place!

I’m done assembling. Time to place the case on a table, connect the monitor, keyboard, mouse and power cable and take a deep breath. No reason to wait any longer.

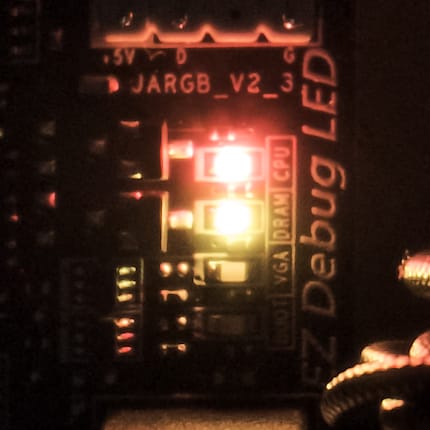

I press the power button. The computer starts up. Fans turn, the LEDs light up – but my screen remains black. The EZ-Debug LEDs (shown in the picture below) shine red for the CPU and yellow for the RAM. In my state of mind at the time – tense, tired, impatient – I don’t interpret this as a normal process, but as a mistake. I disconnect the power and go troubleshooting.

The RAM’s placed correctly. Everything’s in place. I take a moment. Then I remember: RAM training. Of course! RAM training is a process where the main board determines optimum memory timings and voltages on its first start-up before the system boots normally. The process takes some time. Sometimes more than you’d like.

I turn it on again, waiting longer this time. The screen lights up after around fifty seconds. A moment of relief – I’m in, in the UEFI. My system’s alive! And from my next boot, the PC starts up as quickly as I expect it to.

After a break, I update the UEFI via a USB flash, set the RAM to 6000 MT/s (EXP01 profile) and go through the most important options. I deactivate MSI Game Boost so that all cores are used, switch off the iGPU, set manual values for Precision Boost Overdrive and deactivate Bluetooth since I’ll be using an adapter instead – the onboard module doesn’t run in Bazzite yet due to missing drivers. I also set the fan curves for my system and CPU. Then I install Windows – not to play games, but to set up the graphics card’s LED bar. Now an orange light wanders around it like in Knight Rider. A detail that nobody needs, but which just belongs in this build.

The next day, I install and configure Bazzite, download my first games, install Proton-GE and, after customising the game start-up settings, launch a game I’ve already started on the PS5 Pro. The Outer Worlds 2 looks like a whole new game using high quality settings. I sit there with my mouth agape and realise how the finicky work over the last few days has paid off.

In its new home in my living room, my console killer – affectionately christened The Machine – isn’t placed directly on the floor. To prevent it from sucking in any dust lint that might be bouncing around, I gift it a platform made from the lower part of a sawn-off wooden structure.

I’m proud of how this little thing, with its matt black, orange accents and useful carrying handle, looks much better next to my huge TV than the PS5 Pro – hardly taking up any space to boot. But I’m not done yet. For example, I haven’t yet tested how well I can get VRR to work at 4K HDR and 120 hertz – ideally in full 4:4:4 colour resolution – via the TV’s HDMI input. At the moment, this is only possible with an AMD card via detours in Linux – using the right DP-to-HDMI adapter. Still, two possible candidates from Cable Matters and Ugreen are ready for me to compare.

I find my muse in everything. When I don’t, I draw inspiration from daydreaming. After all, if you dream, you don’t sleep through life.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all